‘The Patriot’ by Nissim Ezekiel

This blog task is assigned by Prakruti Bhatt Ma'am (Department of English, MKBU).

Question : Comment on the ironic mode of ‘The Patriot’ by Nissim Ezekiel

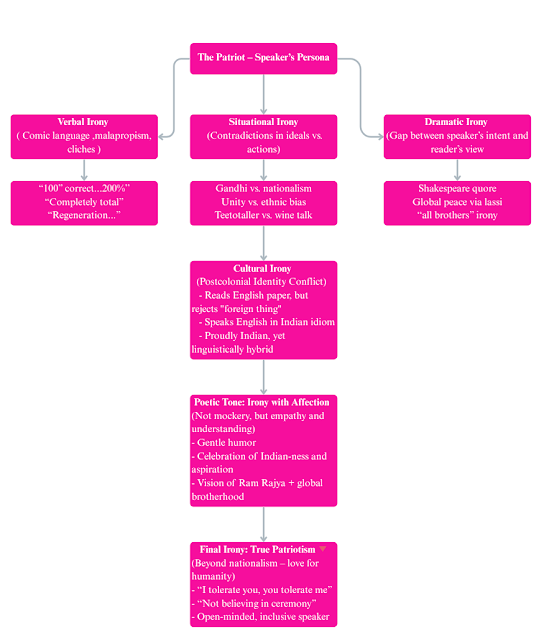

Nissim Ezekiel’s The Patriot is a brilliant example of Indian English poetry that employs irony not merely as a rhetorical device but as the very soul of the poem’s voice and structure. Through the figure of the speaker — a well-meaning, simplistic, and idealistic Indian citizen — Ezekiel crafts an ironic commentary on language, politics, identity, cultural dislocation, and misplaced nationalism. The irony in this poem operates on multiple layers — linguistic, cultural, ideological, and personal — and forms a complex, nuanced engagement with modern Indian consciousness.

1. Verbal Irony: A Comic Tone with Serious Undertones

At the most apparent level, the irony in The Patriot arises from the speaker’s malapropisms, awkward constructions, and hybridized use of Indian-English, which at first glance might seem merely comic.

For example:

"Wine is for the drunkards only. / What do you think of the prospects of world peace?"

Here, the speaker’s sudden leap from a moral observation about alcohol to a question about world peace is comically abrupt. But Ezekiel’s humor is not to ridicule — it is affectionate. The verbal irony lies in how the speaker earnestly attempts to engage in global discourse with limited linguistic tools, unintentionally creating humor — yet never mockery. His statements, like “Ancient Indian Wisdom is 100% correct, I should say even 200% correct,” are naïve in expression but sincere in sentiment.

2. Dramatic Irony: The Gap Between Intention and Perception

Dramatic irony emerges from the gap between what the speaker intends to say and what the reader perceives. The speaker aspires to be taken seriously — he reads The Times of India to improve his English, quotes Shakespeare (“Friends, Romans, Countrymen...”), and discusses global politics and Indian philosophy. However, his speech is riddled with errors and clichés:

“Be patiently, brothers and sisters.”

The reader sees the struggle of a common man trying to articulate noble thoughts in a foreign tongue, and the tragicomic result is deeply ironic. But again, Ezekiel doesn’t ask us to laugh at this man, but to see the irony in the postcolonial condition — where English is both a means of empowerment and a symbol of alienation. The speaker is ironically caught between love for his country and a desire for global belonging, making his patriotism a paradox of sincerity and confusion.

3. Situational Irony: The Paradox of Patriotism

The title “The Patriot” itself is ironic. The speaker denounces violence (“I am standing for peace and non-violence”) and praises Gandhi, but in the same breath, he stereotypes other nations:

“Pakistan behaving like this, / China behaving like that…”

He also mentions Indian unity — “All men are brothers, no?” — but immediately points out internal divisions:

“In India also / Gujaratis, Maharashtrians, Hindi Wallahs / All brothers – / Though some are having funny habits.”

This situational irony highlights the contradictions within nationalist ideologies — the ideal of unity versus the reality of division. The speaker dreams of Ram Rajya (a utopian India), but his views are laced with unconscious prejudices and simplifications. In this, Ezekiel critiques not just the speaker, but the larger societal discourse of patriotism that oscillates between genuine pride and naïve insularity.

4. Irony of Language and Colonial Legacy

Ezekiel’s deliberate use of Indian English or “Babu English” is a key source of irony. Lines like:

“Not that I am ever tasting the wine. / I’m the total teetotaller, completely total,”

are endearingly clumsy but reflect a deep postcolonial truth — how colonized societies internalize the colonizer’s language but adapt it to their own idiom. The irony is that while the speaker attempts to assert his identity and patriotism through English, he does so in a way that reveals the lasting imprint of colonialism. His English is not “perfect,” yet it is authentic — a hybrid tongue, both comic and valid.

This linguistic irony also carries political weight: it points to the tensions in post-independence India between the indigenous and the imported, the spiritual and the material, the Gandhian ideal and the consumerist reality.

5. Irony as Cultural Critique

Ezekiel does not use irony to undermine the speaker’s sincerity but to reveal the ironies of modern Indian life. The speaker laments that young people are “Too much going for fashion and foreign thing,” even as he himself quotes Shakespeare and reads an English-language newspaper. The ironic juxtaposition of his words and actions reflect the cultural disorientation of the Indian middle class, caught between traditional values and modern influences.

Even the offer of lassi as a superior drink to wine is symbolic irony — it’s a nationalist gesture (asserting Indian traditions), but offered in the language of colonial legacy, highlighting the clash and coexistence of cultures.

6. Irony and Affection: The Tone of the Poet

Perhaps the most important dimension of irony in this poem is Ezekiel’s tone. Unlike harsh satire, Ezekiel’s ironic mode is affectionate, humorous, and understanding. He does not ridicule the speaker for his limitations. Instead, he honors the sincerity, simplicity, and moral clarity of a man who, despite his lack of polish, dreams of peace and unity.

By the end, the speaker becomes a lovable, well-intentioned figure who believes in peace, drinks lassi, quotes Shakespeare, and believes Ram Rajya is coming. These lines are not sarcastic, but hopeful — the irony becomes a tool for empathy rather than mockery.

Conclusion: The Patriot’s Irony is Human, Not Cruel

In The Patriot, Nissim Ezekiel employs irony not as a weapon to demean but as a lens to reveal the complex contradictions of postcolonial Indian identity. The ironic mode here is tender, nuanced, and multi-faceted — a mix of humor, sadness, confusion, and clarity. Through this figure of the “common man,” Ezekiel captures the tragicomic essence of Indian patriotism, which is caught between Gandhian idealism, colonial inheritance, linguistic insecurity, and cultural hybridity.

Thus, The Patriot is ironic — but it is also deeply human. Its laughter is never at the cost of the speaker’s dignity. Instead, Ezekiel invites us to see ourselves — our confusions, aspirations, and hypocrisies — mirrored in this voice. The poem, through irony, becomes both a critique and a celebration.

Question : Nissim Ezekiel as the True Patriot

Nissim Ezekiel (1924–2004), often hailed as the father of modern Indian English poetry, occupies a significant position in post-independence Indian literature. Among his many poems, “The Patriot” is a fine example of his ability to blend satire, irony, and social commentary with deep concern for his nation. While on the surface the poem appears humorous—written in broken, Indianized English—it is in fact a profound meditation on the concept of patriotism, especially in the Indian context. Ezekiel emerges not only as a critic of the superficialities of nationalism but also as a true patriot, someone who questions his society in order to reform it.

1. The Satirical Mode and National Identity

Ezekiel’s use of comic errors, wrong syntax, and colloquial English in “The Patriot” is not mere parody. It reflects the linguistic struggles of common Indians in articulating modern ideals, especially in English, the language of both colonial oppression and modern progress. The exaggerated style—“I am standing for peace and non-violence”—captures the rhetorical enthusiasm of pseudo-patriots, but beneath the irony lies Ezekiel’s genuine commitment to Gandhian ideals of peace and non-violence.

By mocking hollow imitations of Gandhian discourse, Ezekiel is not ridiculing Gandhi himself but rather the superficial appropriation of his principles. In this way, he positions himself as a true patriot, one who believes patriotism must go beyond words into practice.

2. Critique of Superficial Patriotism

The poem reveals Ezekiel’s disapproval of shallow nationalism, where individuals declare love for the country in public but imitate Western culture blindly in private. For instance, the poet-patriot laments that the “modern generation is neglecting” ancient Indian wisdom and is “too much going for fashion and foreign thing.” The tone is humorous, but Ezekiel is genuinely disturbed by the growing cultural mimicry, consumerism, and erosion of authentic Indian values after independence.

This dual stance—criticism of both blind Western imitation and hollow traditionalism—shows Ezekiel’s balanced outlook. He is not a blind nationalist but a critical one, which is the hallmark of a true patriot.

3. Patriotism Rooted in Self-Reflection

What sets Ezekiel apart is his insistence on self-criticism as a mode of patriotism. While many poets and leaders glorified the nation uncritically, Ezekiel chose to expose its weaknesses—its corruption, hypocrisy, poverty, and pretensions. His patriotism is not performative but reformative. By holding a mirror to society, he hoped to inspire genuine change.

This aligns with Rabindranath Tagore’s idea that true love for the nation lies not in blind adoration but in striving for its moral and spiritual progress. Ezekiel’s poetry, especially “The Patriot”, works in this same direction.

4. Gandhian Ideals and the Indian Psyche

The poem echoes Gandhian thought, especially the stress on peace, non-violence, and indigenous wisdom. However, Ezekiel portrays how ordinary Indians fail to live up to these ideals. The speaker’s comic diction reflects a gap between ideals and practice. Yet, by emphasizing the importance of these Gandhian values, Ezekiel asserts their relevance in modern India.

Thus, Ezekiel can be seen as a true patriot in the Gandhian sense: someone who promotes moral awakening and insists on ethical self-discipline, rather than merely chanting slogans of nationalism.

5. Universalism in Patriotism

Ezekiel also broadens patriotism to a global scale. By questioning “Why world is fighting fighting / Why all people of world / Are not following Mahatma Gandhi,” the poet emphasizes universal peace. His patriotism transcends narrow nationalism and aspires for international brotherhood. This aligns with the cosmopolitan element of Ezekiel’s identity as an Indian Jewish poet, deeply rooted in Indian culture yet open to global human values.

6. The Poet’s Indian Identity

Ezekiel was sometimes questioned for his Indian-ness due to his Jewish background. Yet through his poems—whether “Night of the Scorpion”, “Background, Casually”, or “The Patriot”—he consistently engaged with the social, cultural, and political realities of India. In “The Patriot”, he does not romanticize India blindly; instead, he criticizes its flaws in order to strengthen it. This act of honest engagement makes him more authentically Indian than those who merely repeat patriotic slogans.

Conclusion

Nissim Ezekiel, through “The Patriot”, emerges as a true patriot not because he glorifies India unconditionally but because he engages with its contradictions and failings in a spirit of reform. His satirical yet sincere voice unmasks the superficiality of hollow nationalism, calls for a revival of Gandhian values, critiques cultural mimicry, and aspires for a universal human brotherhood. True patriotism, as Ezekiel demonstrates, lies in honest self-criticism and a constant striving for the nation’s moral, cultural, and spiritual growth.

In this sense, Ezekiel is not just a poet of irony but a poet of national conscience—an intellectual who used his art to question, refine, and strengthen the idea of India.

Step 2: Group Discussion Report

1. Which poem and questions were discussed by the group?

Our group discussed Nissim Ezekiel’s dramatic monologue “The Patriot.” Each member contributed from a different angle:

- Rutvi Pal: About the poet, Nissim Ezekie

- Devangini Vyas: Plot summary of the poem

- Shrusti Chaudhari: Critical analysis

- Trupti Hadiya: Stanza-wise thematic study

- Rajdeep Bavaliya: Dual interpretation—satire vs. affectionate portrayal

- Sagar Bokadiya: Question of whether broken English is satirical, sympathetic, or both

- Krishna Vala: Style and form

The central questions revolved around the poet’s purpose, the speaker’s voice, the balance between humor and respect, and the cultural implications of Ezekiel’s language.

2. Was there any unique approach or technique used by your group to discuss the topic?

Yes. Instead of randomly exchanging ideas, we divided the discussion systematically. Each participant focused on one dimension of the poem—biography, summary, themes, critical debate, and style. This technique of role-based division helped us avoid repetition and made the conversation comprehensive. We also compared two interpretative frameworks—satire and affection—which deepened the discussion.

3. Who led the discussion or contributed most to the discussion?

While the discussion was collaborative, Rajdeep Bavaliya contributed significantly by foregrounding the tension between satire and affection. His points encouraged further debate, especially when linked with Sagar’s question on whether the humor was mocking or sympathetic. However, Shrusti’s critical analysis also played a key role in shaping the direction of the conversation.

4. Did everyone contribute equally?

Yes, each member prepared in advance and shared insights. Some, like Rajdeep and Sagar, spoke more at length because their topics opened up debates, while others—such as Rutvi and Devangini—provided foundational knowledge that anchored the discussion. Thus, contributions were not identical in length but balanced in importance.

5. Which points were easy and which ones were difficult for everyone in your group to understand?

Easy Points:

- Rutvi’s contextual background on Ezekiel’s life and works was simple to grasp.

- Devangini’s plot summary gave a clear entry point into the poem.

Difficult Points:

- Rajdeep’s exploration of satire versus sympathy was intellectually demanding, as it required weighing two contradictory interpretations.

- Sagar’s question about the function of broken English demanded nuanced thinking about language as both satire and empathy.

- Krishna’s stylistic analysis of free verse, allusions, and linguistic patterns also required extra effort from the group.

Learning Outcome

The group discussion on Nissim Ezekiel’s “The Patriot” enabled us to achieve several important outcomes. We developed a clear contextual understanding of the poet’s life and his role in shaping modern Indian English poetry, which gave us a strong foundation for interpreting the poem. Through the plot summary and stanza-wise thematic study, we deepened our comprehension of both the surface narrative and the underlying cultural tensions within the poem. The debate on satire versus affection enhanced our critical thinking, as we learned how a single text can sustain multiple interpretations and how irony can function with both humor and compassion. Our analysis of Ezekiel’s use of Indian English further made us aware of language as both a comic device and a marker of cultural authenticity in postcolonial literature. The structured, role-based method of discussion improved our collaborative skills, ensuring that every member’s preparation added value to the dialogue. Most importantly, the exercise strengthened our analytical confidence by encouraging us to balance textual evidence with interpretative arguments. Finally, we recognized the continuing relevance of Ezekiel’s critique of superficial patriotism, reminding us that literature often mirrors contemporary challenges of nationalism, identity, and communication.

References :

Ezekiel, Nissim. “The Patriot.” All Poetry, 1977, allpoetry.com/poem/8592073-The-Patriot-by-Nissim-Ezekiel.

Krishnankutty, Pia. “Nissim Ezekiel, a Pioneer of Indian-English Poetry, Was Bound by Layers of His Identity.” ThePrint, 16 Dec. 2019, theprint.in/theprint-profile/nissim-ezekiel-a-pioneer-of-indian-english-poetry-was-bound-by-layers-of-his-identity/334326.

“Nissim Ezekiel - Poems by the Famous Poet.” All Poetry, https://allpoetry.com/Nissim-Ezekiel.

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment